Henry IV Part One holds a special place in my Shakespeare heart as it is not only one of my absolute favourite amongst his plays, but one which I have had the good fortune to see numerous marvellous productions of, including the terrific Royal Shakespeare Company version of the early 1990s, in which Robert Stephens as Falstaff gave the finest performance I have ever seen by anyone on any stage, anywhere. And without comparing myself in any way to that aforementioned great actor, I myself have played numerous scenes from this play over the years, as Falstaff, Prince Hal and Henry the Fourth himself, and thoroughly enjoyed every moment doing so. There have also been some brilliant televised versions, most recently as part of The Hollow Crown series, and I recommend this to anyone curious about the play.

Thus, revisiting the text is both a joyful experience and a slightly dangerous one. Joyful because of memories evoked from previous encounters with the play on stage or on screen; dangerous because such memories can easily influence the impartiality of one’s reading. A colourful character like Falstaff may be seen in numerous ways, but as one reads his lines it is so very, very tempting to conjour up performances of the past. I should state, right away, that I am a huge Falstaff fan, and consider him the finest comic character ever created, so this entry will probably be more slanted to him than to any of the play’s other characters, but that is not to say they are any less interesting in their own right. Falstaff, after all, is essentially nothing more than a sidekick, the amusing supporting role, who (as is so often the case) creates such a mark that his character towers above all others in people’s minds, and leaves us wanting more, much more –fortunately, Shakespeare quickly ”got” this, and the character will appear in two more plays, including the direct sequel to this one. Here he represents one extreme –we are drawn to him much as Prince Hal is, and though we may be frequently appalled by his behaviour, we are fascinated by his audacity and sheer mastery of life and living to the full.

However, the play is titled Henry the Fourth (in nature and character the king is Falstaff’s direct opposite), and the serious action of the play concerns Henry's uneasy reign and his attempts to quell rebellion from disgruntled former allies who have now turned against him. There is a tenseness about Henry that prevails throughout, and he is both burdened with feelings of guilt about his own accession to the throne (by overthrowing Richard II), and exasperated by the seeming inadequacy of his heir, the young Prince Hal, whose happy-go-lucky, carefree lifestyle of drinking and partying with miscreants like Falstaff, is anything but what the King expects or needs from his successor. The king regards his son as a failure, a loser, and admires far more in this respect the other Henry of the play –Hotspur, the son of his main enemy who seems to embody all the traits and character that the king’s own son lacks. And really, the central conflict of the play is this personal one between father and son, rather than the grander conflict of warring factions. Thus, the play is essentially very personal and immediate, and gripping too because we are right in there seeing the king trying to hold things together in both his kingdom and his family. The ironic conceit, of course is that everyone encountering the play knows (or should know) that Prince Hal will come up to scratch and later become the most illustrious and heroic of all English Kings, Henry V, and Shakespeare drops a few hints about this here and there, and part of the brilliance of Henry IV Part One is the way Hal is suspended between the influence of Falstaff and his crowd on one side and the King and court and his duty on the other. Though both are important to him he cannot play to both masters, and it is through learning from both and choosing between them that we see him becoming the great king to be.

Aside from all this Henry IV Part One is a glorious patchwork of England at this time. The many memorable scenes in the tavern seem ageless –though nominally set in the early1400s they would be instantly recognizable to Elizabethan audiences who first saw the play, and are just as much so today –every pub has its braggarts, its gullible hangers-on, its storytellers and its pranksters. And there are plenty of memorable set-pieces, both in this tavern setting and elsewhere throughout the play. My personal favourite is Falstaff’s boasting of how he fought off an attack by two... four... seven... nine... ruffians, his lies and exaggerations growing from line to line. And anyone looking for colourful insults to add to their repertoire need look no further than the marvellously salty exchanges of name-calling between Prince Hal and Falstaff. Shakespeare must surely have enjoyed creating them as much as we delight in hearing them! (see the exchange under Favourite line(s) below for an example)

Finally, I must mention briefly two of the female characters that inhabit this otherwise very male play. Lady Percy (the wife of Hotspur) is a relatively small but memorable part, with a great speech and scene with her husband in Act II, and one almost wishes she featured more in the play. And Mistress Quickly, hostess of the Boar’s Head, makes the first of her several appearances in Shakespeare’s works. She, like the other ”regulars” of the tavern can very easily be overplayed or presented as mere bawdy caricatures, but I think there is a lot more to her than this, and intelligent productions cotton on to that without negating her comic role. She is a bit like a mother hen to all these miscreants, someone they so often take for granted, but without whom they (and the play itself) would be all the poorer.

Favourite Line(s):

Prince Hal (of Falstaff)

..this sanguine coward, this bed-presser, this horse-back-breaker, this huge hill of flesh–

Falstaff (to Prince Hal)

’Sblood, you starveling, you eel-skin, you dried neat’s-tongue, you bull’s pizzle, you stock-fish – O for breath to utter what is like thee! – you tailor’s yard, you sheath, you bow-case, you vile standing tuck!

(Act II, Sc.4)

Character I would most like to play: Falstaff (again) or Hotspur

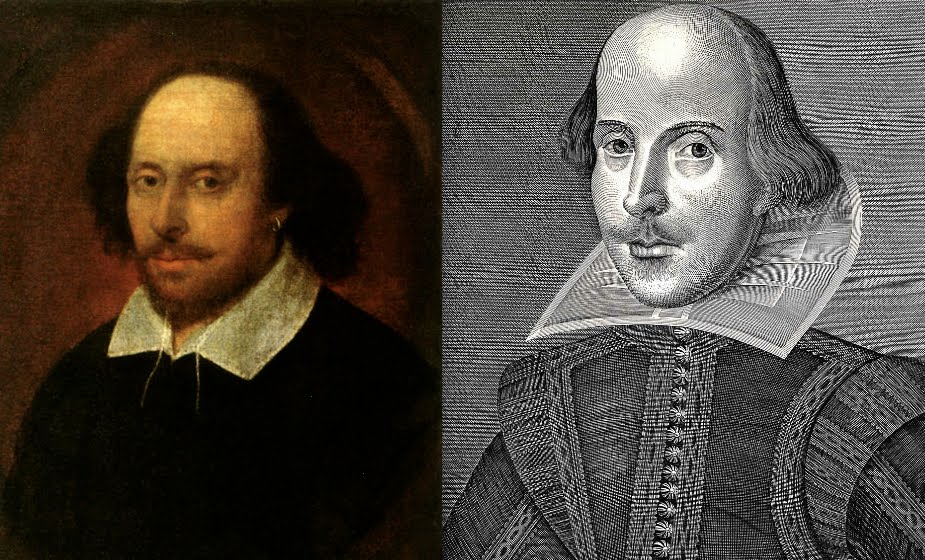

A blog in celebration of the immortal William Shakespeare and my chronological journey through his works during the course of a year -ShakesYear ! "You are welcome, masters, welcome all..."

Saturday 18 June 2016

Thursday 2 June 2016

THE MERCHANT OF VENICE –The One With the Pound of Flesh!

The Comical History of the Merchant of Venice, or Otherwise Called the Jew of Venice (as it is titled in the First Folio) is undoubtedly one of Shakespeare’s most famous plays (and among of my own personal favourites), but both it and the character of Shylock have a certain notoriety because of the unavoidable question of anti-semitism. Shylock is not a particularly big part (he’s only in a few scenes), but it’s a great part, such that it dominates the play in much the way Falstaff will in Henry IV soon after. He is undoubtedly the villain of the piece, but I don’t find the presentation of him to be narrower or unfairer than that of any other of Shakespeare’s creations. Certainly the play deals with the issue of anti-semitism, but it is seen primarily in the way Shylock is treated by many of the other characters rather than his own character –I think Shylock is a fascinating character, and to call him a caricature or stereotype is to negate the subtext of so much of his words and actions. Essentially, I think he is a very sad person, but that does not mean we have to be sympathetic to him or condone his actions.

The play is ostensibly described as a comedy, but this is an ill-fitting coat; much of the action of the play is far from comic, and the play falls more into a category best described as ”a mixed bag” –part tragedy, part comedy, part romance, but, unlike many other such unclassifiable plays, one that somehow almost always seems to work on stage. I think this is primarily because there is at its heart a really good story, or rather several stories, linked through good characters and terrific set pieces, like the choosing of the caskets and Act IV’s famous court scene. This is the first time I have actually read the whole play. Previously, I have only read extracts or worked on speeches from it, but I knew the play well nonetheless, having seen several wonderful productions, both on stage and screen. Each of these had their outstanding moments, but the best overall stage production I’ve seen was that produced at Birmingham Rep in 1997, directed by Bill Alexander. Trevor Nunn’s tired production at the Royal National Theatre in 2000 was by far the worst, but even in that the power of the story shone through. I also recall a very odd Danish production directed by Staffan Holm at Copenhagen’s Royal Theatre back in 1993 which concluded by having an enormous golden ball roll across the stage, Indiana Jones-style, while the song Mad About the Boy blared over the loudspeakers (I really must do a blog entry on bizarre and whacky innovations in Shakespeare productions!)

Favourite Line:

Lorenzo:

The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treason, stratagems and spoils.

(Act 5, Sc.1)

Character I would most like to play: Shylock (but Portia would be fun too)

The play is ostensibly described as a comedy, but this is an ill-fitting coat; much of the action of the play is far from comic, and the play falls more into a category best described as ”a mixed bag” –part tragedy, part comedy, part romance, but, unlike many other such unclassifiable plays, one that somehow almost always seems to work on stage. I think this is primarily because there is at its heart a really good story, or rather several stories, linked through good characters and terrific set pieces, like the choosing of the caskets and Act IV’s famous court scene. This is the first time I have actually read the whole play. Previously, I have only read extracts or worked on speeches from it, but I knew the play well nonetheless, having seen several wonderful productions, both on stage and screen. Each of these had their outstanding moments, but the best overall stage production I’ve seen was that produced at Birmingham Rep in 1997, directed by Bill Alexander. Trevor Nunn’s tired production at the Royal National Theatre in 2000 was by far the worst, but even in that the power of the story shone through. I also recall a very odd Danish production directed by Staffan Holm at Copenhagen’s Royal Theatre back in 1993 which concluded by having an enormous golden ball roll across the stage, Indiana Jones-style, while the song Mad About the Boy blared over the loudspeakers (I really must do a blog entry on bizarre and whacky innovations in Shakespeare productions!)

Favourite Line:

Lorenzo:

The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treason, stratagems and spoils.

(Act 5, Sc.1)

Character I would most like to play: Shylock (but Portia would be fun too)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)