Some academics place the writing of this play after the two other Henry VI plays, and as I am following the chronology as set out in The Oxford Shakespeare which argues this, I have now read this after the other two. And I have to say my gut feeling is to disagree with the view of the esteemed editors of that volume in terms of its chronology –I believe it was written before the others; chiefly because it seems to be very uneven in style and less mature in construction. I do agree with them in that it was probably written by several people, Shakespeare being one of them, and it is fairly easy to spot or ”feel” the different voices (or pens). Thus there are parts that are more effective and well-written than others, and the overall effect can be a bit disjointing. There are good scenes and plenty of drama, but in general the development of character is less mature than in the following two parts, which is logical considering those plays are far more likely to be the work of just one writer – our boy Shakespeare. Here though it seems to be a collaboration. It works as a whole, and is full of energy but as a play it is uneven and it is not surprisingly performed even less frequently than the other two plays about Henry the Sixth.

This is not to say it is a disaster or not worth reading –quite the contrary: early Shakespeare is some ways more rewarding to read than those great masterpieces of his mature years that are on so high a level of excellence and so skillfully written that we are not immediately aware of the craftwork. It is with the early plays that we get a sense of him at work, trying out things, learning his craft and sharpening his ever playful use of language. Henry VI Part 1 is like the work of an apprentice –but a very gifted one, who will later use things he learned and tried out here to greater effect.

There are two characters that stand out for me in the large cast of characters –Talbot, the pragmatic, loyal commander who has no time for the petty squabbles and intrigues of those who are supposedly on his side and who simply gets on with the job. The scene where his young son turns up to fight alongside him is the best scene in the play, and one of Shakespeare’s best father/son scenes. It’s brilliantly heightened by having their lines rhyme, creating a bond between them that is poetical and deeply moving. It’s almost operatic in style, and it is intriguing to wonder whether Shakespeare is putting something of his relationship with his own father in these lines. I choose to think so.

The other stand-out character is, of course, Joan La Pucelle –better known to us as Joan of Arc. She is a truly fascinating historical character in her own right and we cannot give Shakespeare credit for creating her, but her part is written with great relish and she electrifies each scene she appears in, without descending into caricature. She is clearly ”the enemy” but Shakespeare by and large presents her in a fair and sympathetic way –or rather a way that allows us to sympathize with her position Her language is that of a true warrior and most of the French nobles around her pale beside her. I found the scenes with her the most rewarding to read, and I think Shakespeare must have enjoyed writing them as they flow so easily.

Henry himself comes across in a rather wishy-washy way here –he is after all only a boy or very young man, and though the play bears his name it is more about the people around him who are all manoeuvering like mad. There is a great deal of family and inter-family squabbling, and once again it does help to have a genealogical table nearby when reading the play, just to untangle some of the relationships and alliances. Sadly, I have yet to see a full stage production of the play, though I remember fondly the English Shakespeare Company’s televised version some years ago which was part of their ”War of the Roses” project.

Favourite Line:

Sir William Lucy

O. were mine eye-balls into bullets turn’d,

That I in rage might shoot them at your faces!

(Act IV, Sc.VII)

Character I would most like to play: Talbot

A blog in celebration of the immortal William Shakespeare and my chronological journey through his works during the course of a year -ShakesYear ! "You are welcome, masters, welcome all..."

Wednesday 24 February 2016

Thursday 18 February 2016

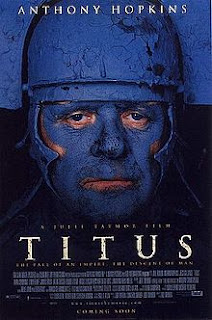

SHAKES-SCREEN: Titus (1999)

Marvellously Shocking!

Having just read the play Titus Andronicus I was eager to take a look at the 1999 film version. I found it an uplifting experience, because though the film was quite different to my own visualization of the story, it was a perfectly consistent modern take that both respected the language and construction of the original play and provided an exciting, personal interpretation –respectful of Shakespeare but true to itself. In fact, I rate it as among the best screen versions of Shakespeare’s work. Perhaps because it also succeeds in balancing on a line that is purely theatrical on one side and purely cinematic on the other –so that though I often feel I am watching a film of a stage production, I never feel constrained by this; for the film is genuinely and richly cinematic. I am also extremely glad that a certain amount of restraint was shown in the direction –it could so easily have been totally overloaded with effects, forced gimmicks and gore, but here the visuals –and impressive they are– never overpower the language and the interaction between the characters.

The performances are of a high level throughout, and the actors are all comfortable with the language, which is a relief because so many other “modern” versions of Shakespeare suffer from an inconsistent mixing of acting styles that distract us momentarily from the story. Here there is no attempt to slur the dialogue to make it seem “real” –it succeeds because it retains its metre and theatricality. I think Anthony Hopkins’ performance is interestingly low-key and playful –the character itself is a difficult one to fully sympathize with– but Hopkins takes us down many different paths. He is both former hard general, ambitious and later grieving father, warm grandfather figure, madman, avenger –a complex character indeed. And again, the restraint in his performance says more than any rant. I also particularly like the pairing of him with Colm Feore as his brother. Alan Cumming gives a very memorable performance as the emperor –I found this character difficult to fully get hold of when I read the play, but the boldness and audacity shown by Cumming makes him very clear –and again it’s never over-the-top as it so easily could be.

I think it does help to know at least something of the play before seeing the film as there is no real explanation of exactly who is who to begin with and this may cause some confusion –the unravelling of characters and their relationships is equally challenging in the opening of the play, so the fault (if it can be called that) lies with Shakespeare. The whole first act is a bit of a mess –perhaps intentionally– and though we are able to work out who is who and what their relationship is to the next person, it does demand a bit of extra concentration at the beginning of the film that could perhaps have benefitted from some form of narration or on-screen signing. This is, however, my only complaint –otherwise I found the film marvellous; utterly shocking, of course, but marvellously shocking!

Titus (1999)

Director: Julie Taymor

With: Anthony Hopkins, Jessica Lange, Alan Cumming, Harry Lennix, Colm Feore

Having just read the play Titus Andronicus I was eager to take a look at the 1999 film version. I found it an uplifting experience, because though the film was quite different to my own visualization of the story, it was a perfectly consistent modern take that both respected the language and construction of the original play and provided an exciting, personal interpretation –respectful of Shakespeare but true to itself. In fact, I rate it as among the best screen versions of Shakespeare’s work. Perhaps because it also succeeds in balancing on a line that is purely theatrical on one side and purely cinematic on the other –so that though I often feel I am watching a film of a stage production, I never feel constrained by this; for the film is genuinely and richly cinematic. I am also extremely glad that a certain amount of restraint was shown in the direction –it could so easily have been totally overloaded with effects, forced gimmicks and gore, but here the visuals –and impressive they are– never overpower the language and the interaction between the characters.

The performances are of a high level throughout, and the actors are all comfortable with the language, which is a relief because so many other “modern” versions of Shakespeare suffer from an inconsistent mixing of acting styles that distract us momentarily from the story. Here there is no attempt to slur the dialogue to make it seem “real” –it succeeds because it retains its metre and theatricality. I think Anthony Hopkins’ performance is interestingly low-key and playful –the character itself is a difficult one to fully sympathize with– but Hopkins takes us down many different paths. He is both former hard general, ambitious and later grieving father, warm grandfather figure, madman, avenger –a complex character indeed. And again, the restraint in his performance says more than any rant. I also particularly like the pairing of him with Colm Feore as his brother. Alan Cumming gives a very memorable performance as the emperor –I found this character difficult to fully get hold of when I read the play, but the boldness and audacity shown by Cumming makes him very clear –and again it’s never over-the-top as it so easily could be.

I think it does help to know at least something of the play before seeing the film as there is no real explanation of exactly who is who to begin with and this may cause some confusion –the unravelling of characters and their relationships is equally challenging in the opening of the play, so the fault (if it can be called that) lies with Shakespeare. The whole first act is a bit of a mess –perhaps intentionally– and though we are able to work out who is who and what their relationship is to the next person, it does demand a bit of extra concentration at the beginning of the film that could perhaps have benefitted from some form of narration or on-screen signing. This is, however, my only complaint –otherwise I found the film marvellous; utterly shocking, of course, but marvellously shocking!

Titus (1999)

Director: Julie Taymor

With: Anthony Hopkins, Jessica Lange, Alan Cumming, Harry Lennix, Colm Feore

Saturday 13 February 2016

TITUS ANDRONICUS –The One With That Human Pie!

...Well! –it is hard to avoid being stunned into such terseness upon completion of reading this play, one I had not previously read or seen on stage and knew only from its notorious reputation for goriness. Several times as I read it I had to put down the text because I was numbed by the horror of what I was reading, for this is Shakespeare’s most sensationally savage play, and unlike that more renowned and stylishly heightened horror piece Macbeth, Titus Andronicus has a rawness and viciousness that is fascinatingly frightening to encounter. Written at a time when there was a trend for gore and sensationalism on stage, with a killing every few minutes, this play was one of Shakespeare’s most produced in his own time and probably is one of the reasons he became so popular a writer. Because it is shockingly ”good” theatre, providing just what the audiences wanted in a horrifyingly seductive way. It works in the same way that horror films do, or roller-coasters for that matter. I’d be fascinated to know how many people have fainted during performances of it, for I’m sure the number must exceed that for any other Shakespeare play. The number of characters who snuff it is also probably one of the highest for his plays; some barely last a moment on stage. But it is the manner of the deaths that is most shocking: This is set in a harsh period of history, centuries before Shakespeare’s own time (which itself wasn’t exactly humane), but serving sons up in pies to their mother is on a whole different level, even as an act of revenge. This is just one of several gruesome scenes that so easily could descend into farce of a very black kind if not seen in the context of the whole play or dealt with very carefully in a production.

It is a dark, troubling, upsetting piece –Shakespeare’s first tragedy, and bears signs of being the work of an enthusiastic but not yet fully developed writer, but it has terrific energy amidst its rawness and a clarity of thought and dialogue that, no matter how we feel about it, makes the lines jump off the page as we read them. And there are some real gems that make us step back a moment from all the gore –like the sobering words of Titus to his brother who has just killed a fly, asking him to consider the fly’s mother and father, for their sorrow at losing a child could be as great as a man’s. This is a terrific little scene that brings in a whole new element to our viewing of the story and of our own lives. Few of us have slaughtered enemies of Rome, but who has not swatted a fly and never given it a second thought? I have always liked such moments of reflection in Shakespeare –and I’ve come to realize that he has them in almost all his plays; moments where we are taken out of the story briefly and presented with an idea, a new angle on things, and this lingers in our mind. In Henry VI Part 3, for instance, there is the speech of Henry reflecting on being a shepherd rather than a king, and this is the same sort of thing. It is part of what makes Shakespeare so great.

I find the character of Titus himself to be quite difficult to fully understand, and though I was able to follow the unfolding story of his misfortune with ease and have sympathy with him in the middle acts, he does to a certain extent bring the tragedy on himself through his treatment of the prisoners he brings back in the opening scenes –killing the eldest son of Queen Tamora, already severely pissed off at being conquered. Her lust for revenge is right up there with Queen Margaret in the previous play (Henry VI Part 3) and with such a capacity for cold-hearted viciousness she makes Lady Macbeth look like a pussy cat. Were just these two characters (Titus and Tamora) pitted against each other, it would be in a sense a fair fight, but the real tragedy of Titus Andronicus is that of the secondary characters, and none more so than Titus’ daughter Lavinia –surely one of Shakespeare’s most unfortunate characters: jilted by the Emperor; her true love killed; ravished by two men; hands cut off: tongue cut out; then finally to be stabbed and killed by her father –her story arc is nothing but woe. Though she has few lines (even when she still has her tongue), she is the human centre of the play. Famously she was played by Vivien Leigh in the 1955 RSC-production with husband Laurence Olivier playing Titus. This is by far the most well-known production of the play. There have been others, of course, but like the other Roman plays of Shakespeare it is not produced very often –its gruesomeness is not necessarily good box-office, and companies wanting to go down a bloody path tend to go for the safer (and shorter) Macbeth. Also, as an early Shakespeare play it is always going to get less attention than the works that follow. But, I stress again: it is gripping ”theatre”, even when read, so do give it a go –if you have a strong constitution.

In my next entry I shall be reviewing the 1999 film adaptation (Titus).

Favourite Line:

Lucius

Bur soft! me thinks I do digress too much,

Citing my worthless praise. O, pardon me !

For when no friends are by, men praise themselves.

(Act V, Sc.III)

Character I would most like to play: Aaron

It is a dark, troubling, upsetting piece –Shakespeare’s first tragedy, and bears signs of being the work of an enthusiastic but not yet fully developed writer, but it has terrific energy amidst its rawness and a clarity of thought and dialogue that, no matter how we feel about it, makes the lines jump off the page as we read them. And there are some real gems that make us step back a moment from all the gore –like the sobering words of Titus to his brother who has just killed a fly, asking him to consider the fly’s mother and father, for their sorrow at losing a child could be as great as a man’s. This is a terrific little scene that brings in a whole new element to our viewing of the story and of our own lives. Few of us have slaughtered enemies of Rome, but who has not swatted a fly and never given it a second thought? I have always liked such moments of reflection in Shakespeare –and I’ve come to realize that he has them in almost all his plays; moments where we are taken out of the story briefly and presented with an idea, a new angle on things, and this lingers in our mind. In Henry VI Part 3, for instance, there is the speech of Henry reflecting on being a shepherd rather than a king, and this is the same sort of thing. It is part of what makes Shakespeare so great.

I find the character of Titus himself to be quite difficult to fully understand, and though I was able to follow the unfolding story of his misfortune with ease and have sympathy with him in the middle acts, he does to a certain extent bring the tragedy on himself through his treatment of the prisoners he brings back in the opening scenes –killing the eldest son of Queen Tamora, already severely pissed off at being conquered. Her lust for revenge is right up there with Queen Margaret in the previous play (Henry VI Part 3) and with such a capacity for cold-hearted viciousness she makes Lady Macbeth look like a pussy cat. Were just these two characters (Titus and Tamora) pitted against each other, it would be in a sense a fair fight, but the real tragedy of Titus Andronicus is that of the secondary characters, and none more so than Titus’ daughter Lavinia –surely one of Shakespeare’s most unfortunate characters: jilted by the Emperor; her true love killed; ravished by two men; hands cut off: tongue cut out; then finally to be stabbed and killed by her father –her story arc is nothing but woe. Though she has few lines (even when she still has her tongue), she is the human centre of the play. Famously she was played by Vivien Leigh in the 1955 RSC-production with husband Laurence Olivier playing Titus. This is by far the most well-known production of the play. There have been others, of course, but like the other Roman plays of Shakespeare it is not produced very often –its gruesomeness is not necessarily good box-office, and companies wanting to go down a bloody path tend to go for the safer (and shorter) Macbeth. Also, as an early Shakespeare play it is always going to get less attention than the works that follow. But, I stress again: it is gripping ”theatre”, even when read, so do give it a go –if you have a strong constitution.

In my next entry I shall be reviewing the 1999 film adaptation (Titus).

Favourite Line:

Lucius

Bur soft! me thinks I do digress too much,

Citing my worthless praise. O, pardon me !

For when no friends are by, men praise themselves.

(Act V, Sc.III)

Character I would most like to play: Aaron

Saturday 6 February 2016

HENRY VI PART 3 –The One With the Paper Crown

Also known as The Third Part of Henry the Sixth, with the Death of the Duke of York (Folio of 1623 title), and The True Tragedy of Richard, Duke of York, and the Death of Good King Henry the Sixth, with the whole Contention between the two houses Lancaster and York (1595 version), this play is my own favourite of the three plays about Henry VI. It’s certainly not the end of the story, because Richard III will soon follow, but it brings together lots of different threads and is in a sense a series of small dramas with no one character dominating throughout, but each having his or her ”moment” as the continuing struggle for power evolves. Thus it is an ensemble piece rather than a ”star” vehicle like Richard III. Richard himself (here still Duke of Gloucester) does steal almost every scene he is in, but it is mostly towards the end of the play that the focus shifts to him –a portent of things to come; and I am quite sure Shakespeare was already looking ahead to writing the play about his reign and looking forward to exploring this fascinating character more. Here Richard is coarser, more direct and more viscerally violent than in the play that bears his name (and where, though just as ruthless, he schemes with such deliciously evil charm). Here in Henry VI Part 3, however, we get much of the background to his character –how and why he became what he is– and quite often some of the latter scenes and speeches from this play are incorporated in productions of Richard III –the Olivier film from 1955 does this, for instance.

Act One of the play is one of the most dramatic of all the history plays, and there are some quite shocking scenes –torture, killing, taunting, and it doesn’t really stop until the end. The tone of the play is extremely grim and frantic, with the crown passing back and forth from side to side like a football, and the war causing the disintegration of moral codes and hardening of hearts as it rolls on. And as an examination of what war does to men, this play is Shakespeare’s harshest. One scene in particular stands out as a striking example of this –scene 5 in Act II, where a father who has inadvertently killed his own son and a son who has killed his own father in battle share the stage and lament, and are observed by King Henry, who is aghast at what he sees. It is one of the few scenes in the play that involves ”common” men, and must have packed as much of punch when it was originally performed as it does when we read it today; it is unusually modern, and quite outside the main line of the story, but it brings the war into instant sobering perspective, both to the king and, through him, the audience. Unfortunately, because this play is so seldom performed the scene is not very well known, but it deserves to be right up there with the best of Shakespeare.

The contrast between Henry and his wife, Queen Margaret, is stretched even further in this play than in Part 2, with Margaret’s viciousness reaching new heights and Henry’s diffidence making him touchingly sympathetic. It’s not that he does not wish to be king; he just would prefer it if the job did not come with so much trouble. And his gentleness among such harshness is curiously alluring. My second favourite scene in the play is the final confrontation between him and Richard who comes to the Tower of London to murder him. In their brief altercation lies all the differences between them, and for a moment or two Henry really shows his fire. This is a great little scene for drama students, by the way; and there are many other similar one-on-one encounters that make terrific workshop pieces. There are also some excellent speeches for both men and women that can be used for auditions. I myself have several times used Henry’s musing on how much more peaceful it would be to be a shepherd than a king (Act II, Sc. 5) for this purpose and in Shakspeare programmes.

The play certainly deserves more recognition and I thoroughly recommend reading it, though once again it does help to have a genealogical table close by to keep track of who is who. You are fortunate if you manage to catch a full production of it because when it is presented it is often an condensed version of Parts 1, 2 and 3, or 2 and 3. The English Shakespeare Company famously performed the whole cycle of history plays in the late 1980s and these were televised and issued on VHS. I hope they pop up on DVD some day as I remember being captivated by the energy of these productions, presented in a contemporary setting on a fairly bare stage which allowed the characters and words and unfolding plot to be in focus. The BBC also produced a fairly good version of this and the other Henry VI plays in their BBC TV Shakespeare series.

Favourite Lines:

Gloucester

But where the fox hath once got in his nose,

He’ll soon fins means to make the body follow.

(Act IV, Sc.7)

Warwick

Why, what is pomp, rule, reign, but earth and dust?

And live we how we can, yet die we must.

(Act V, Sc.2)

plus

All of Richard’s ”plan” speech

(Act II, Sc.2)

Character I would most like to play: Richard, Duke of Gloucester

Act One of the play is one of the most dramatic of all the history plays, and there are some quite shocking scenes –torture, killing, taunting, and it doesn’t really stop until the end. The tone of the play is extremely grim and frantic, with the crown passing back and forth from side to side like a football, and the war causing the disintegration of moral codes and hardening of hearts as it rolls on. And as an examination of what war does to men, this play is Shakespeare’s harshest. One scene in particular stands out as a striking example of this –scene 5 in Act II, where a father who has inadvertently killed his own son and a son who has killed his own father in battle share the stage and lament, and are observed by King Henry, who is aghast at what he sees. It is one of the few scenes in the play that involves ”common” men, and must have packed as much of punch when it was originally performed as it does when we read it today; it is unusually modern, and quite outside the main line of the story, but it brings the war into instant sobering perspective, both to the king and, through him, the audience. Unfortunately, because this play is so seldom performed the scene is not very well known, but it deserves to be right up there with the best of Shakespeare.

The contrast between Henry and his wife, Queen Margaret, is stretched even further in this play than in Part 2, with Margaret’s viciousness reaching new heights and Henry’s diffidence making him touchingly sympathetic. It’s not that he does not wish to be king; he just would prefer it if the job did not come with so much trouble. And his gentleness among such harshness is curiously alluring. My second favourite scene in the play is the final confrontation between him and Richard who comes to the Tower of London to murder him. In their brief altercation lies all the differences between them, and for a moment or two Henry really shows his fire. This is a great little scene for drama students, by the way; and there are many other similar one-on-one encounters that make terrific workshop pieces. There are also some excellent speeches for both men and women that can be used for auditions. I myself have several times used Henry’s musing on how much more peaceful it would be to be a shepherd than a king (Act II, Sc. 5) for this purpose and in Shakspeare programmes.

The play certainly deserves more recognition and I thoroughly recommend reading it, though once again it does help to have a genealogical table close by to keep track of who is who. You are fortunate if you manage to catch a full production of it because when it is presented it is often an condensed version of Parts 1, 2 and 3, or 2 and 3. The English Shakespeare Company famously performed the whole cycle of history plays in the late 1980s and these were televised and issued on VHS. I hope they pop up on DVD some day as I remember being captivated by the energy of these productions, presented in a contemporary setting on a fairly bare stage which allowed the characters and words and unfolding plot to be in focus. The BBC also produced a fairly good version of this and the other Henry VI plays in their BBC TV Shakespeare series.

Favourite Lines:

Gloucester

But where the fox hath once got in his nose,

He’ll soon fins means to make the body follow.

(Act IV, Sc.7)

Warwick

Why, what is pomp, rule, reign, but earth and dust?

And live we how we can, yet die we must.

(Act V, Sc.2)

plus

All of Richard’s ”plan” speech

(Act II, Sc.2)

Character I would most like to play: Richard, Duke of Gloucester

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)