I remember being pleasantly enchanted by this rather winsome film version of Shakespeare’s romantic comedy/fantasy when it first appeared, and it certainly looked beautiful on the big screen with its gorgeous, warm cinematography, composition and production design. It created a pleasant, warm feeling in the audience, delivering a comforting experience, and drawing a few chuckles here and there; smiles rather than belly laughs. For here the comedy is fairly genteel, and often also quite melancholic –there is always another dimension to each moment of laughter -a story beyond, especially with the tradesmen who put their heart into performing, despite their lack of any real talent. Their preparations for and ultimate performance of ”Pyramus and Thisbe” is where much of the comedy of the play lies, but in this film the traditional comic moments are toned down a great deal. I admire the restrained performances of both individuals and the amateur group as an ensemble, because it is so easy to go over the top with their part in the story. Here we smile affectionately rather than laugh mockingly, and our smiles are warm and sympathetic, as they sometimes are when someone in the family performs at a wedding or similar despite a lack of talent. Kevin Kline as Bottom naturally takes much of the limelight, and gives his character a whole deeper life than is normally seen, as does the very underrated Roger Rees as Peter Quince –he gives an immensely dignified and rather beautiful performance here, full of subtle details that I only really appreciated upon viewing the film again.

I found many of the magical scenes with the fairies to be quite mesmerizing, and the careful use of special effects was just right in creating moments of fantasy and wonder without overwhelming the picture. Much of the beauty of the play lies in the lines spoken by Oberon and Titania and Puck, and Rupert Everett, Michelle Pfeiffer and Stanley Tucci give great respect to the language and poetry of Shakespeare, without falling to the traps of prettifying it or making it bombastic –it’s poetry, yet living dramatical interaction too. By and large, I think most of the cast do quite well with the text, making it alive and personal, and I certainly am not one of those who despair at American voices uttering Shakespeare; quite the contrary. Here, there is a nice mix of American and British voices, and it is to the film’s credit.

If I were pushed to criticize the film it would be for its lack of ”edge” or danger –passion, if you like. This applies both to the two pairs of young lovers, and the fairy characters and their escapades. Everything is a little too mellow and tame, so that we are lulled more than provoked. A little more spice or audacity would have perked things up considerably, and the story certainly gives room for and even suggests this.

But the director has his own vision of the play and is at least consequent in his presentation of that, and it’s perfectly acceptable. The interesting thing is that the play may be tackled in many different ways, and the ”world” that is presented here in all its lush, green, dream-like beauty is no less valid than other more provocative versions of Shakespeare’s magical comedy.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1999)

Director: Michael Hoffman

With: Rupert Everett, Michelle Pfeiffer, Stanley Tucci, Kevin Kline, Christian Bale, Anna Friel, Calista Flockhart, Roger Rees, David Strathairn

A blog in celebration of the immortal William Shakespeare and my chronological journey through his works during the course of a year -ShakesYear ! "You are welcome, masters, welcome all..."

Showing posts with label Films. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Films. Show all posts

Thursday, 19 May 2016

Friday, 22 April 2016

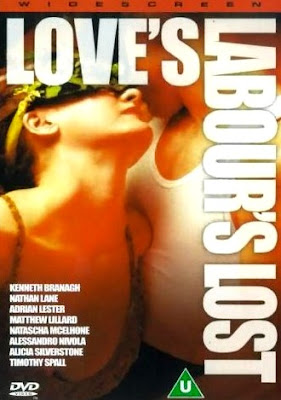

SHAKES-SCREEN: Love’s Labor’s Lost (2000)

Dancing With Shakespeare!

"Dancing With Shakespeare" is the direct translation of the title this film was given in Norway, and it is quite an apt description not only of the film’s content, but the fundamental, gnawing weakness of the film: a play that above all plays with language seems ill at ease in a jacket marked ”dancing”. When you dance with Shakespeare you don’t want to get out of step, and Love’s Labour’s Lost doesn’t quite come together. And it’s very sad because it’s a film you so much want to work, because its heart is in the right place, and its intentions are good and creative and exciting and bold. Yes, it’s enjoyable and frothy, silly and sincere in equal measures, beautifully shot with a camera that plays a part in the best Hollywood-golden-age manner, and sometimes it’s very funny and works beautifully. But frequently the novelty of turning one of Shakespeare’s most language-reliant comedies into a nostalgic romantic musical simply works against itself, and the result is then flat rather than uplifting. And this is not because people don’t try –everyone involved in the film really gives it a good go, and clearly wants to try to make it come off. It very nearly does, but not quite –there is an unevenness about it that keeps us from getting fully engrossed in what we see, and this is the sort of film that needs that to work.

I was lucky enough to see this film originally at a special screening introduced by Kenneth Branagh and Alicia Silverstone, which boosted the preview audience into a higher gear of excitement and expectation than would be usual, so the experience was a little like the prospect of drinking lots of champagne –delightful, but somehow never as good as the idea of it!

Upon re-watching the film recently, I think the film in fact rather more resembles one of those very fancy, colourful cocktails you order when on holiday, with tiny umbrellas and exotic fruit and flowers sticking out and looking enormously tempting on the menu and when brought to you, but always somewhat impractical to drink and with ingredients that don’t quite mix together satisfyingly enough. With Love’s Labour’s Lost the conceit of transforming Shakespeare’s rich ideas into classic Hollywood musical numbers to bring across certain moods and emotional moments is a fun recipe, but it seems to me to clash too often with the actual text the film is based on. Now, admittedly much of Shakespeare’s play is very obscure and difficult to understand compared to other plays he wrote, and severe editing was going to be inevitable; but putting in musical number after musical number as a replacement seems more a way of padding the film to arrive at a decent length rather than really moving the story along. In fact, many of the musical numbers –skillfully and cheekily staged though some of them are– just get in the way of things, and frequently I found myself wishing that Branagh had been even more faithful to Shakespeare and instead kept in more of the actual play itself. Thus I was pleasantly surprised to find a number of deleted scenes on the DVD of the film that sadly never made it to the final cut. I think these should have been kept in because they help make more sense of the story.

The diversity of performers that comprise the cast is quite interesting and there are some magnificent individual performances, though again the range of different styles doesn’t always gel on screen. To a certain extent this was also true of Branagh’s Much Ado About Nothing and Hamlet. Everyone is doing their own little film, and sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Timothy Spall’s Don Armado is perhaps one of the most outrageous performances ever seen on screen, but it is totally in keeping with the character as written. And both he and Nathan Lane (as Costard the clown) bring an essential element of sadness to their otherwise comic roles that is very moving. But the double quartet of lovers that form the central romantic story of the film is a very mixed bag indeed. Branagh understandably gives the plum role of Berowne to himself and sells his Shakespeare with that admirable deftness that is uniquely his, but he is really too old for the part and this works against him here. I also feel at times he should have directed himself more astutely or had better assistance at doing so, for it is largely the scenes in which he does not appear that work best –simply because at such times he, as director, is able to concentrate fully on the other performances. The film also seems unable to break itself totally free from its stageiness to become the truly filmic musical it aspires to be.

So, I am quite ambivalent about this film. I DO like and enjoy it, and applaud Branagh for tackling a lesser-known Shakespeare comedy, and with such gusto, but I SO wish I were able to like it more and be fully satisfied by it –and by the greater film that is in its heart..

Love’s Labour’s Lost (2000)

Director: Kenneth Branagh

With: Kenneth Branagh, Timothy Spall, Alicia Silverstone, Nathan Lane, Matthew Lillard, Geraldine McEwan, Richard Briers, Alessandro Nivola. Adrian Lester

"Dancing With Shakespeare" is the direct translation of the title this film was given in Norway, and it is quite an apt description not only of the film’s content, but the fundamental, gnawing weakness of the film: a play that above all plays with language seems ill at ease in a jacket marked ”dancing”. When you dance with Shakespeare you don’t want to get out of step, and Love’s Labour’s Lost doesn’t quite come together. And it’s very sad because it’s a film you so much want to work, because its heart is in the right place, and its intentions are good and creative and exciting and bold. Yes, it’s enjoyable and frothy, silly and sincere in equal measures, beautifully shot with a camera that plays a part in the best Hollywood-golden-age manner, and sometimes it’s very funny and works beautifully. But frequently the novelty of turning one of Shakespeare’s most language-reliant comedies into a nostalgic romantic musical simply works against itself, and the result is then flat rather than uplifting. And this is not because people don’t try –everyone involved in the film really gives it a good go, and clearly wants to try to make it come off. It very nearly does, but not quite –there is an unevenness about it that keeps us from getting fully engrossed in what we see, and this is the sort of film that needs that to work.

I was lucky enough to see this film originally at a special screening introduced by Kenneth Branagh and Alicia Silverstone, which boosted the preview audience into a higher gear of excitement and expectation than would be usual, so the experience was a little like the prospect of drinking lots of champagne –delightful, but somehow never as good as the idea of it!

Upon re-watching the film recently, I think the film in fact rather more resembles one of those very fancy, colourful cocktails you order when on holiday, with tiny umbrellas and exotic fruit and flowers sticking out and looking enormously tempting on the menu and when brought to you, but always somewhat impractical to drink and with ingredients that don’t quite mix together satisfyingly enough. With Love’s Labour’s Lost the conceit of transforming Shakespeare’s rich ideas into classic Hollywood musical numbers to bring across certain moods and emotional moments is a fun recipe, but it seems to me to clash too often with the actual text the film is based on. Now, admittedly much of Shakespeare’s play is very obscure and difficult to understand compared to other plays he wrote, and severe editing was going to be inevitable; but putting in musical number after musical number as a replacement seems more a way of padding the film to arrive at a decent length rather than really moving the story along. In fact, many of the musical numbers –skillfully and cheekily staged though some of them are– just get in the way of things, and frequently I found myself wishing that Branagh had been even more faithful to Shakespeare and instead kept in more of the actual play itself. Thus I was pleasantly surprised to find a number of deleted scenes on the DVD of the film that sadly never made it to the final cut. I think these should have been kept in because they help make more sense of the story.

The diversity of performers that comprise the cast is quite interesting and there are some magnificent individual performances, though again the range of different styles doesn’t always gel on screen. To a certain extent this was also true of Branagh’s Much Ado About Nothing and Hamlet. Everyone is doing their own little film, and sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Timothy Spall’s Don Armado is perhaps one of the most outrageous performances ever seen on screen, but it is totally in keeping with the character as written. And both he and Nathan Lane (as Costard the clown) bring an essential element of sadness to their otherwise comic roles that is very moving. But the double quartet of lovers that form the central romantic story of the film is a very mixed bag indeed. Branagh understandably gives the plum role of Berowne to himself and sells his Shakespeare with that admirable deftness that is uniquely his, but he is really too old for the part and this works against him here. I also feel at times he should have directed himself more astutely or had better assistance at doing so, for it is largely the scenes in which he does not appear that work best –simply because at such times he, as director, is able to concentrate fully on the other performances. The film also seems unable to break itself totally free from its stageiness to become the truly filmic musical it aspires to be.

So, I am quite ambivalent about this film. I DO like and enjoy it, and applaud Branagh for tackling a lesser-known Shakespeare comedy, and with such gusto, but I SO wish I were able to like it more and be fully satisfied by it –and by the greater film that is in its heart..

Love’s Labour’s Lost (2000)

Director: Kenneth Branagh

With: Kenneth Branagh, Timothy Spall, Alicia Silverstone, Nathan Lane, Matthew Lillard, Geraldine McEwan, Richard Briers, Alessandro Nivola. Adrian Lester

Wednesday, 6 April 2016

SHAKES-SCREEN: Richard III (1995)

I rate this as one of my favourite Shakespeare films!

Placing one of Shakespeare’s history plays in another specific historical period is always a bit of a risky thing. Such a ploy more frequently works better on stage than on screen –our suspension of belief being somewhat more liberal in a theatre than in front of a screen. Often the transfer in time is to a “generic” future historical setting, with a bit of this period and a bit of that. Sometimes this works, sometimes it doesn’t. The reason I think placing this version of Richard III in the 1930s works so well is the faithfulness to that conceit, which is carried through impeccably in every detail, though never in a forced or laboured way. It is a clever, often witty, adaptation of Shakespeare’s masterly examination of one man’s relentless pursuit of power –and has both elegance and a style of its own aside from the play it is based on, and a healthy respect of Shakespeare’s glorious language and characters.

Perhaps the language is what may deter some people from fully enjoying this, though I would argue that it merely demands paying a little more attention to what is being said than when watching a “normal” film. Contrary to what many may think, Shakespeare’s language is not difficult or obscure –quite the opposite– but you do need to listen to it! Here, of course, you are helped by having some of the finest actors around, with not only great command of that language, but the ability to present clearly defined yet complex characters, so that we are able to keep track of who is who in the web of family connections and intrigue. The film is much shorter than the play (Shakespeare’s longest), and does away with some characters and combines others into one figure. This polishes the narrative somewhat, but does not take anything vital away from the unfolding tale. I do, however, recommend going back to the original play if you enjoy this film, because it will give an even broader appreciation of the story. And what a story!

Centre-stage (or centre-screen, in this case) is Ian McKellen as Richard. It is surely his finest screen performance, and is certainly the one that really made me appreciate his work when I first saw the film upon its original release. Like Olivier before him, his Richard is a performance perfected through countless performances on stage in the role, and with devilish charm he milks each ounce of scheming, determination and wickedness from his scenes. Yet, unlike Olivier, he also shares with us a certain clumsiness and even pathos, which though it does not excuse in any way his actions does give us some understanding of why he has become the grotesque figure he is.

Of the other performances I particularly like Jim Broadbent’s take on the Duke of Buckingham –his beaming face has eyes of steel, and he seems to be silently scheming, listening, and judging in every scene in which he appears. Anette Bening also does a terrific job and makes more much of her part than is written. But all the actors do wonders in conveying their own particular “angsts” and concerns. Seeing the film again now, I only wish it was longer and we saw even more of some of them.

Finally I must applaud the designers of the production –both visual and aural– who have created a totally believable alternate English setting of the 1930s. It is both familiar and alien at the same time –which is what makes the film’s central idea so chilling: That such a thing could have happened in England at this time as it did in Germany and Italy and Spain. Shakespeare may have been writing about the 15th century, but the scheming of despots, hungry for power, goes on and on and on.

Richard III (1995)

Director: Richard Loncraine

With: Ian McKellen, Nigel Hawthorne, Anette Bening, Maggie Smith, Jim Broadbent, Robert Downey, Jr.

Placing one of Shakespeare’s history plays in another specific historical period is always a bit of a risky thing. Such a ploy more frequently works better on stage than on screen –our suspension of belief being somewhat more liberal in a theatre than in front of a screen. Often the transfer in time is to a “generic” future historical setting, with a bit of this period and a bit of that. Sometimes this works, sometimes it doesn’t. The reason I think placing this version of Richard III in the 1930s works so well is the faithfulness to that conceit, which is carried through impeccably in every detail, though never in a forced or laboured way. It is a clever, often witty, adaptation of Shakespeare’s masterly examination of one man’s relentless pursuit of power –and has both elegance and a style of its own aside from the play it is based on, and a healthy respect of Shakespeare’s glorious language and characters.

Perhaps the language is what may deter some people from fully enjoying this, though I would argue that it merely demands paying a little more attention to what is being said than when watching a “normal” film. Contrary to what many may think, Shakespeare’s language is not difficult or obscure –quite the opposite– but you do need to listen to it! Here, of course, you are helped by having some of the finest actors around, with not only great command of that language, but the ability to present clearly defined yet complex characters, so that we are able to keep track of who is who in the web of family connections and intrigue. The film is much shorter than the play (Shakespeare’s longest), and does away with some characters and combines others into one figure. This polishes the narrative somewhat, but does not take anything vital away from the unfolding tale. I do, however, recommend going back to the original play if you enjoy this film, because it will give an even broader appreciation of the story. And what a story!

Centre-stage (or centre-screen, in this case) is Ian McKellen as Richard. It is surely his finest screen performance, and is certainly the one that really made me appreciate his work when I first saw the film upon its original release. Like Olivier before him, his Richard is a performance perfected through countless performances on stage in the role, and with devilish charm he milks each ounce of scheming, determination and wickedness from his scenes. Yet, unlike Olivier, he also shares with us a certain clumsiness and even pathos, which though it does not excuse in any way his actions does give us some understanding of why he has become the grotesque figure he is.

Of the other performances I particularly like Jim Broadbent’s take on the Duke of Buckingham –his beaming face has eyes of steel, and he seems to be silently scheming, listening, and judging in every scene in which he appears. Anette Bening also does a terrific job and makes more much of her part than is written. But all the actors do wonders in conveying their own particular “angsts” and concerns. Seeing the film again now, I only wish it was longer and we saw even more of some of them.

Finally I must applaud the designers of the production –both visual and aural– who have created a totally believable alternate English setting of the 1930s. It is both familiar and alien at the same time –which is what makes the film’s central idea so chilling: That such a thing could have happened in England at this time as it did in Germany and Italy and Spain. Shakespeare may have been writing about the 15th century, but the scheming of despots, hungry for power, goes on and on and on.

Richard III (1995)

Director: Richard Loncraine

With: Ian McKellen, Nigel Hawthorne, Anette Bening, Maggie Smith, Jim Broadbent, Robert Downey, Jr.

Thursday, 24 March 2016

SHAKES-SCREEN: Richard III (1955)

Courting the Camera.

Of the three Shakespeare plays that Laurence Olivier directed and starred in, Richard III is my favourite, though I think both Henry V (1944) and Hamlet (1948) are more filmic and wide-reaching visually. Richard III is more stagey, more theatrical. This is not necessarily a bad thing, for it captures probably one of the finest, most delicious performances ever in a context that respects its theatrical heritage (Olivier famously played Richard on stage earlier). And there is something about the very construction of the play that is very theatrical –essentially it is a series of small dramas or set pieces: scenes that in themselves are works of art, and beautifully crafted that way by Shakespeare. The staginess works best when Olivier speaks directly to us, because then he is using an unconventional film device (actors don’t normally talk to the camera) to improve upon a common theatrical device, creating a bond between role and audience. That this is not employed throughout the play is as much Shakespeare’s fault as Olivier’s, because it is written that way –we get no direct address from Richard in the crucial demise at the battle, and are thus relegated back to being observers rather than “confidents”.

Upon rewatching it, I was struck by how much what seeing was itself an historical document –of a style of acting and staging that perhaps to us now seems dated, but which at the time was perfectly relevant and true. When diction counted for something and clarity of expression and utterance was all important. Some of the performances come across as more dated than others, perhaps because of their shameless heightened theatricality. This is particularly true of some of lesser characters whose have no star appeal to buoy them up and are dependent merely upon their craft. Yet someone like Ralph Richardson is such an interesting screen personality that his performance –like that of Olivier’s– remains fresh and vivid. Michael Gough does wonders with his small part, and Claire Bloom is marvellous –the scene in which her character is wooed by Richard is one of my favourite in both the film and in all of Shakespeare.

People have remarked upon the unevenness of the final act, with a sunny Spanish landscape so clearly standing in for soggy England that it distracts our attention away from the narrative; the theatricality is gone and we are suddenly made of this being a film location. The way this necessary shift from studio to outdoors is handled is much more deftly achieved in Olivier’s earlier Henry V, which also has a more satisfying battle scene, but that was written more precisely too; the battle scene in Shakespeare’s Richard III only has a few lines and few directions so any film version will have to expand upon these. I think in this case there must have been many logistic difficulties with the location filming because this section of the film is sadly not on par with what has come before.

Yet, though I may seem negative, I am merely pointing things that I feel could have been better. They do not affect my enjoyment of the film, nor my high regard of Olivier as a director and performer. And of all Shakespeare films, this is the one I return to again and again.

Richard III (1955)

Director: Laurence Olivier

With: Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, Claire Bloom, Cedric Hardwicke

Of the three Shakespeare plays that Laurence Olivier directed and starred in, Richard III is my favourite, though I think both Henry V (1944) and Hamlet (1948) are more filmic and wide-reaching visually. Richard III is more stagey, more theatrical. This is not necessarily a bad thing, for it captures probably one of the finest, most delicious performances ever in a context that respects its theatrical heritage (Olivier famously played Richard on stage earlier). And there is something about the very construction of the play that is very theatrical –essentially it is a series of small dramas or set pieces: scenes that in themselves are works of art, and beautifully crafted that way by Shakespeare. The staginess works best when Olivier speaks directly to us, because then he is using an unconventional film device (actors don’t normally talk to the camera) to improve upon a common theatrical device, creating a bond between role and audience. That this is not employed throughout the play is as much Shakespeare’s fault as Olivier’s, because it is written that way –we get no direct address from Richard in the crucial demise at the battle, and are thus relegated back to being observers rather than “confidents”.

Upon rewatching it, I was struck by how much what seeing was itself an historical document –of a style of acting and staging that perhaps to us now seems dated, but which at the time was perfectly relevant and true. When diction counted for something and clarity of expression and utterance was all important. Some of the performances come across as more dated than others, perhaps because of their shameless heightened theatricality. This is particularly true of some of lesser characters whose have no star appeal to buoy them up and are dependent merely upon their craft. Yet someone like Ralph Richardson is such an interesting screen personality that his performance –like that of Olivier’s– remains fresh and vivid. Michael Gough does wonders with his small part, and Claire Bloom is marvellous –the scene in which her character is wooed by Richard is one of my favourite in both the film and in all of Shakespeare.

People have remarked upon the unevenness of the final act, with a sunny Spanish landscape so clearly standing in for soggy England that it distracts our attention away from the narrative; the theatricality is gone and we are suddenly made of this being a film location. The way this necessary shift from studio to outdoors is handled is much more deftly achieved in Olivier’s earlier Henry V, which also has a more satisfying battle scene, but that was written more precisely too; the battle scene in Shakespeare’s Richard III only has a few lines and few directions so any film version will have to expand upon these. I think in this case there must have been many logistic difficulties with the location filming because this section of the film is sadly not on par with what has come before.

Yet, though I may seem negative, I am merely pointing things that I feel could have been better. They do not affect my enjoyment of the film, nor my high regard of Olivier as a director and performer. And of all Shakespeare films, this is the one I return to again and again.

Richard III (1955)

Director: Laurence Olivier

With: Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, Claire Bloom, Cedric Hardwicke

Thursday, 18 February 2016

SHAKES-SCREEN: Titus (1999)

Marvellously Shocking!

Having just read the play Titus Andronicus I was eager to take a look at the 1999 film version. I found it an uplifting experience, because though the film was quite different to my own visualization of the story, it was a perfectly consistent modern take that both respected the language and construction of the original play and provided an exciting, personal interpretation –respectful of Shakespeare but true to itself. In fact, I rate it as among the best screen versions of Shakespeare’s work. Perhaps because it also succeeds in balancing on a line that is purely theatrical on one side and purely cinematic on the other –so that though I often feel I am watching a film of a stage production, I never feel constrained by this; for the film is genuinely and richly cinematic. I am also extremely glad that a certain amount of restraint was shown in the direction –it could so easily have been totally overloaded with effects, forced gimmicks and gore, but here the visuals –and impressive they are– never overpower the language and the interaction between the characters.

The performances are of a high level throughout, and the actors are all comfortable with the language, which is a relief because so many other “modern” versions of Shakespeare suffer from an inconsistent mixing of acting styles that distract us momentarily from the story. Here there is no attempt to slur the dialogue to make it seem “real” –it succeeds because it retains its metre and theatricality. I think Anthony Hopkins’ performance is interestingly low-key and playful –the character itself is a difficult one to fully sympathize with– but Hopkins takes us down many different paths. He is both former hard general, ambitious and later grieving father, warm grandfather figure, madman, avenger –a complex character indeed. And again, the restraint in his performance says more than any rant. I also particularly like the pairing of him with Colm Feore as his brother. Alan Cumming gives a very memorable performance as the emperor –I found this character difficult to fully get hold of when I read the play, but the boldness and audacity shown by Cumming makes him very clear –and again it’s never over-the-top as it so easily could be.

I think it does help to know at least something of the play before seeing the film as there is no real explanation of exactly who is who to begin with and this may cause some confusion –the unravelling of characters and their relationships is equally challenging in the opening of the play, so the fault (if it can be called that) lies with Shakespeare. The whole first act is a bit of a mess –perhaps intentionally– and though we are able to work out who is who and what their relationship is to the next person, it does demand a bit of extra concentration at the beginning of the film that could perhaps have benefitted from some form of narration or on-screen signing. This is, however, my only complaint –otherwise I found the film marvellous; utterly shocking, of course, but marvellously shocking!

Titus (1999)

Director: Julie Taymor

With: Anthony Hopkins, Jessica Lange, Alan Cumming, Harry Lennix, Colm Feore

Having just read the play Titus Andronicus I was eager to take a look at the 1999 film version. I found it an uplifting experience, because though the film was quite different to my own visualization of the story, it was a perfectly consistent modern take that both respected the language and construction of the original play and provided an exciting, personal interpretation –respectful of Shakespeare but true to itself. In fact, I rate it as among the best screen versions of Shakespeare’s work. Perhaps because it also succeeds in balancing on a line that is purely theatrical on one side and purely cinematic on the other –so that though I often feel I am watching a film of a stage production, I never feel constrained by this; for the film is genuinely and richly cinematic. I am also extremely glad that a certain amount of restraint was shown in the direction –it could so easily have been totally overloaded with effects, forced gimmicks and gore, but here the visuals –and impressive they are– never overpower the language and the interaction between the characters.

The performances are of a high level throughout, and the actors are all comfortable with the language, which is a relief because so many other “modern” versions of Shakespeare suffer from an inconsistent mixing of acting styles that distract us momentarily from the story. Here there is no attempt to slur the dialogue to make it seem “real” –it succeeds because it retains its metre and theatricality. I think Anthony Hopkins’ performance is interestingly low-key and playful –the character itself is a difficult one to fully sympathize with– but Hopkins takes us down many different paths. He is both former hard general, ambitious and later grieving father, warm grandfather figure, madman, avenger –a complex character indeed. And again, the restraint in his performance says more than any rant. I also particularly like the pairing of him with Colm Feore as his brother. Alan Cumming gives a very memorable performance as the emperor –I found this character difficult to fully get hold of when I read the play, but the boldness and audacity shown by Cumming makes him very clear –and again it’s never over-the-top as it so easily could be.

I think it does help to know at least something of the play before seeing the film as there is no real explanation of exactly who is who to begin with and this may cause some confusion –the unravelling of characters and their relationships is equally challenging in the opening of the play, so the fault (if it can be called that) lies with Shakespeare. The whole first act is a bit of a mess –perhaps intentionally– and though we are able to work out who is who and what their relationship is to the next person, it does demand a bit of extra concentration at the beginning of the film that could perhaps have benefitted from some form of narration or on-screen signing. This is, however, my only complaint –otherwise I found the film marvellous; utterly shocking, of course, but marvellously shocking!

Titus (1999)

Director: Julie Taymor

With: Anthony Hopkins, Jessica Lange, Alan Cumming, Harry Lennix, Colm Feore

Tuesday, 26 January 2016

SHAKES-SCREEN: The Taming of the Shrew (1967)

Alongside my chronological reading of the plays of Shakespeare I will be revisiting or watching for the first time various filmed and televised versions of many of them, and posting a few remarks on them. First out is Franco Zeffirelli’s version of The Taming of the Shrew.

Shakespearean comedy has not always fared too well on film, and there are far fewer successful film versions of these than there are of the tragedies and other dramas. But there are one or two that do stand out and The Taming of the Shrew belongs to this select group. I think there are several reasons for this: the casting -which is magnificent and inspired; the acting -which balances just on the edge of ”over-the-top” without succumbing to out-and-out farce; the pace -which is boisterous and bonny; and the profusion of little touches and details of scene, direction and picture. It is like a series of rather fine paintings from the Renaissance that are brought before us and taken away just as we start to think a little deeper about what is being shown. Here, as in most good comedy, we are never allowed to dwell too long before the next chapter unfolds. Zeffirelli’s vision for this film is very theatrical, almost operatic, and he sees it through, so that it is a well-rounded whole; it’s certainly beautifully designed and fascinating to look at. I quite understand why the choice was made to focus on the main story of Petruchio and Katharina (Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor are terrific together), though purists may claim their histrionics flourish at the expense of the sub-plot, which is more heavily cut compared to its place in the original play.In Shakespeare's play much of the business involving the wooing of Bianca contains references that are less accessible to modern audiences than they would be to those watching in the 1590s. But I think quite enough is kept to retain the gist and thrust of the scheming. Bianca as a character does remain rather bland though, as indeed she does in the play.

The film does away with the framing device –the "Induction" that Shakespeare used in his play, so here there is no opening scene in England with Christopher Sly and thus what we are shown is presented as ”real” and not as a play being presented to this drunken character. Many stage productions do away with this frame device too, and most people are probably unaware that it is even part of the story.

There are many fine and colourful performances here, right across the board, but more importantly the cast works particularly well as an ensemble, each actor embracing the communal spirit of the piece and firing off each other. I find Michael Hordern deliciously perfect as the distraught father of the two girls . His facial expressions speak a thousand words and I think he gives one of the finest performances of his career; as does Burton. And Elizabeth Taylor is just fantastic.

The Taming of the Shrew (1967)

Director: Franco Zeffirelli

With: Richard Burton, Eizabeth Taylor, Michael York, Cyril Cusack, Michael Hordern, Alan Webb, Natasha Pyne, Alfred Lynch, Victor Spinetti

Shakespearean comedy has not always fared too well on film, and there are far fewer successful film versions of these than there are of the tragedies and other dramas. But there are one or two that do stand out and The Taming of the Shrew belongs to this select group. I think there are several reasons for this: the casting -which is magnificent and inspired; the acting -which balances just on the edge of ”over-the-top” without succumbing to out-and-out farce; the pace -which is boisterous and bonny; and the profusion of little touches and details of scene, direction and picture. It is like a series of rather fine paintings from the Renaissance that are brought before us and taken away just as we start to think a little deeper about what is being shown. Here, as in most good comedy, we are never allowed to dwell too long before the next chapter unfolds. Zeffirelli’s vision for this film is very theatrical, almost operatic, and he sees it through, so that it is a well-rounded whole; it’s certainly beautifully designed and fascinating to look at. I quite understand why the choice was made to focus on the main story of Petruchio and Katharina (Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor are terrific together), though purists may claim their histrionics flourish at the expense of the sub-plot, which is more heavily cut compared to its place in the original play.In Shakespeare's play much of the business involving the wooing of Bianca contains references that are less accessible to modern audiences than they would be to those watching in the 1590s. But I think quite enough is kept to retain the gist and thrust of the scheming. Bianca as a character does remain rather bland though, as indeed she does in the play.

The film does away with the framing device –the "Induction" that Shakespeare used in his play, so here there is no opening scene in England with Christopher Sly and thus what we are shown is presented as ”real” and not as a play being presented to this drunken character. Many stage productions do away with this frame device too, and most people are probably unaware that it is even part of the story.

There are many fine and colourful performances here, right across the board, but more importantly the cast works particularly well as an ensemble, each actor embracing the communal spirit of the piece and firing off each other. I find Michael Hordern deliciously perfect as the distraught father of the two girls . His facial expressions speak a thousand words and I think he gives one of the finest performances of his career; as does Burton. And Elizabeth Taylor is just fantastic.

The Taming of the Shrew (1967)

Director: Franco Zeffirelli

With: Richard Burton, Eizabeth Taylor, Michael York, Cyril Cusack, Michael Hordern, Alan Webb, Natasha Pyne, Alfred Lynch, Victor Spinetti

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)