Well, now we come to the play that is many people’s favourite; the one that instantly puts a smile on their face when it is mentioned, that open their eyes to enchantment, and wonder, and delighted amusement. Like no other Shakespeare play it brings out the child in all of us, and it’s no surprise that it’s particularly popular with children and young people; for many of them it is their first encounter with Shakespeare, either as a text or in performance, and it’s one of the most frequently produced of all Shakespeare’s plays and somehow (magically perhaps?) almost always seems to work. You can do almost anything with it and still pull it off, as countless productions have shown. I’ve seen it played by children, by teenagers, by students, by amateur groups and by seasoned professionals; and done as high comedy, lyrical and mysterious musical pageant, puppet show and circus-like physical theatre. I’ve seen it done on a bare stage, and on incredibly elaborate sets. I’ve even seen it set on a rubbish tip! And all of these wildly diverse productions have worked, and given their audience joy and laughter and wonder and delight. Quite a feat!

When I went back to revisit the text itself I had memories of all these productions whizzing about in my head, and it was often difficult to try and examine the play objectively, as if reading it for the first time. Yet I was instantly struck by just how gloriously the words and lines flow from the page, especially after coming straight from Love’s Labour’s Lost which took so much more effort to fully understand and appreciate. With A Midsummer Night’s Dream Shakespeare really steps up a gear, and this seems to me to be a turning point in his output: the moment when his already great talent becomes truly sublime. Everything he has learned and experimented with comes together here in a perfect play: poetry, comedy, romance, construction, plot, clarity and a true grasp of theatre in all its possibilities and devices. It’s a light play –one could say it floats; yet it is never trivial. Its characters may not at first seem deep, but they are as living and memorable as any in Shakespeare. We recognize and can smile at some of them (anyone who has ever been involved in any form of theatre will have known numerous Nick Bottoms and Peter Quinces and Francis Flutes), whilst others are far from anything in our experience, except perhaps in our dreams.

Yes, there’s something for everyone here: at least three separate stories and a multitude of stories within each story, yet all held and coming together beautifully, like a delicate silk web. And I adore the poetry and imagery of the play as much as I adore the comedy and pathos of the amateur players, whose keenness makes up for their lack of talent, and who are treated much more gently in this play by their audience than the players at the end of the previous play, Love’s Labour’s Lost.

If you are new to this play then do try to see a production of it before picking up the text; let yourself be swept away by its poetry and music and delightful charm before delving into the brilliant and elegant craftsmanship of the piece more closely.

Favourite Line:

Theseus:

”His speech was like a tangled chain –nothing impaired, but all disordered.”

(Act 5, Sc.1)

And almost all of Puck’s lines

Character I would most like to play: Puck

A blog in celebration of the immortal William Shakespeare and my chronological journey through his works during the course of a year -ShakesYear ! "You are welcome, masters, welcome all..."

Wednesday, 27 April 2016

Saturday, 23 April 2016

Happy Birthday!

I couldn't let today pass without posting something, but with so much "Shakespeare activity" going on all over the place there has hardly been time. It's Shakespeare heaven out there! So excuse my very theatrical pose in front of his statue in Central Park, taken a few years ago.

Though naturally most of the attention has been connected with the fact that its 400 years today since William died, I have chosen rather to celebrate that it's 452 years today since he was born; because, if truth be told, Shakespeare never really died; he's still with us, and in so many ways, and he still reaches out to us and is relevant and touching and entertaining and endlessly fascinating. It's so moving to see the many, many tributes to him coming from all over the world, and from people of all ages, and I hope today may bring even more people to his work. So tonight's toast will be one of gratitude and continued admiration and deep respect: Happy Birthday, Mr. Shakespeare! Thy eternal summer shall not fade.

Though naturally most of the attention has been connected with the fact that its 400 years today since William died, I have chosen rather to celebrate that it's 452 years today since he was born; because, if truth be told, Shakespeare never really died; he's still with us, and in so many ways, and he still reaches out to us and is relevant and touching and entertaining and endlessly fascinating. It's so moving to see the many, many tributes to him coming from all over the world, and from people of all ages, and I hope today may bring even more people to his work. So tonight's toast will be one of gratitude and continued admiration and deep respect: Happy Birthday, Mr. Shakespeare! Thy eternal summer shall not fade.

Friday, 22 April 2016

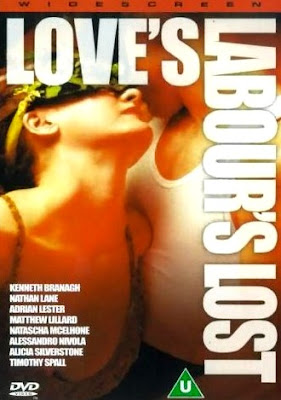

SHAKES-SCREEN: Love’s Labor’s Lost (2000)

Dancing With Shakespeare!

"Dancing With Shakespeare" is the direct translation of the title this film was given in Norway, and it is quite an apt description not only of the film’s content, but the fundamental, gnawing weakness of the film: a play that above all plays with language seems ill at ease in a jacket marked ”dancing”. When you dance with Shakespeare you don’t want to get out of step, and Love’s Labour’s Lost doesn’t quite come together. And it’s very sad because it’s a film you so much want to work, because its heart is in the right place, and its intentions are good and creative and exciting and bold. Yes, it’s enjoyable and frothy, silly and sincere in equal measures, beautifully shot with a camera that plays a part in the best Hollywood-golden-age manner, and sometimes it’s very funny and works beautifully. But frequently the novelty of turning one of Shakespeare’s most language-reliant comedies into a nostalgic romantic musical simply works against itself, and the result is then flat rather than uplifting. And this is not because people don’t try –everyone involved in the film really gives it a good go, and clearly wants to try to make it come off. It very nearly does, but not quite –there is an unevenness about it that keeps us from getting fully engrossed in what we see, and this is the sort of film that needs that to work.

I was lucky enough to see this film originally at a special screening introduced by Kenneth Branagh and Alicia Silverstone, which boosted the preview audience into a higher gear of excitement and expectation than would be usual, so the experience was a little like the prospect of drinking lots of champagne –delightful, but somehow never as good as the idea of it!

Upon re-watching the film recently, I think the film in fact rather more resembles one of those very fancy, colourful cocktails you order when on holiday, with tiny umbrellas and exotic fruit and flowers sticking out and looking enormously tempting on the menu and when brought to you, but always somewhat impractical to drink and with ingredients that don’t quite mix together satisfyingly enough. With Love’s Labour’s Lost the conceit of transforming Shakespeare’s rich ideas into classic Hollywood musical numbers to bring across certain moods and emotional moments is a fun recipe, but it seems to me to clash too often with the actual text the film is based on. Now, admittedly much of Shakespeare’s play is very obscure and difficult to understand compared to other plays he wrote, and severe editing was going to be inevitable; but putting in musical number after musical number as a replacement seems more a way of padding the film to arrive at a decent length rather than really moving the story along. In fact, many of the musical numbers –skillfully and cheekily staged though some of them are– just get in the way of things, and frequently I found myself wishing that Branagh had been even more faithful to Shakespeare and instead kept in more of the actual play itself. Thus I was pleasantly surprised to find a number of deleted scenes on the DVD of the film that sadly never made it to the final cut. I think these should have been kept in because they help make more sense of the story.

The diversity of performers that comprise the cast is quite interesting and there are some magnificent individual performances, though again the range of different styles doesn’t always gel on screen. To a certain extent this was also true of Branagh’s Much Ado About Nothing and Hamlet. Everyone is doing their own little film, and sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Timothy Spall’s Don Armado is perhaps one of the most outrageous performances ever seen on screen, but it is totally in keeping with the character as written. And both he and Nathan Lane (as Costard the clown) bring an essential element of sadness to their otherwise comic roles that is very moving. But the double quartet of lovers that form the central romantic story of the film is a very mixed bag indeed. Branagh understandably gives the plum role of Berowne to himself and sells his Shakespeare with that admirable deftness that is uniquely his, but he is really too old for the part and this works against him here. I also feel at times he should have directed himself more astutely or had better assistance at doing so, for it is largely the scenes in which he does not appear that work best –simply because at such times he, as director, is able to concentrate fully on the other performances. The film also seems unable to break itself totally free from its stageiness to become the truly filmic musical it aspires to be.

So, I am quite ambivalent about this film. I DO like and enjoy it, and applaud Branagh for tackling a lesser-known Shakespeare comedy, and with such gusto, but I SO wish I were able to like it more and be fully satisfied by it –and by the greater film that is in its heart..

Love’s Labour’s Lost (2000)

Director: Kenneth Branagh

With: Kenneth Branagh, Timothy Spall, Alicia Silverstone, Nathan Lane, Matthew Lillard, Geraldine McEwan, Richard Briers, Alessandro Nivola. Adrian Lester

"Dancing With Shakespeare" is the direct translation of the title this film was given in Norway, and it is quite an apt description not only of the film’s content, but the fundamental, gnawing weakness of the film: a play that above all plays with language seems ill at ease in a jacket marked ”dancing”. When you dance with Shakespeare you don’t want to get out of step, and Love’s Labour’s Lost doesn’t quite come together. And it’s very sad because it’s a film you so much want to work, because its heart is in the right place, and its intentions are good and creative and exciting and bold. Yes, it’s enjoyable and frothy, silly and sincere in equal measures, beautifully shot with a camera that plays a part in the best Hollywood-golden-age manner, and sometimes it’s very funny and works beautifully. But frequently the novelty of turning one of Shakespeare’s most language-reliant comedies into a nostalgic romantic musical simply works against itself, and the result is then flat rather than uplifting. And this is not because people don’t try –everyone involved in the film really gives it a good go, and clearly wants to try to make it come off. It very nearly does, but not quite –there is an unevenness about it that keeps us from getting fully engrossed in what we see, and this is the sort of film that needs that to work.

I was lucky enough to see this film originally at a special screening introduced by Kenneth Branagh and Alicia Silverstone, which boosted the preview audience into a higher gear of excitement and expectation than would be usual, so the experience was a little like the prospect of drinking lots of champagne –delightful, but somehow never as good as the idea of it!

Upon re-watching the film recently, I think the film in fact rather more resembles one of those very fancy, colourful cocktails you order when on holiday, with tiny umbrellas and exotic fruit and flowers sticking out and looking enormously tempting on the menu and when brought to you, but always somewhat impractical to drink and with ingredients that don’t quite mix together satisfyingly enough. With Love’s Labour’s Lost the conceit of transforming Shakespeare’s rich ideas into classic Hollywood musical numbers to bring across certain moods and emotional moments is a fun recipe, but it seems to me to clash too often with the actual text the film is based on. Now, admittedly much of Shakespeare’s play is very obscure and difficult to understand compared to other plays he wrote, and severe editing was going to be inevitable; but putting in musical number after musical number as a replacement seems more a way of padding the film to arrive at a decent length rather than really moving the story along. In fact, many of the musical numbers –skillfully and cheekily staged though some of them are– just get in the way of things, and frequently I found myself wishing that Branagh had been even more faithful to Shakespeare and instead kept in more of the actual play itself. Thus I was pleasantly surprised to find a number of deleted scenes on the DVD of the film that sadly never made it to the final cut. I think these should have been kept in because they help make more sense of the story.

The diversity of performers that comprise the cast is quite interesting and there are some magnificent individual performances, though again the range of different styles doesn’t always gel on screen. To a certain extent this was also true of Branagh’s Much Ado About Nothing and Hamlet. Everyone is doing their own little film, and sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Timothy Spall’s Don Armado is perhaps one of the most outrageous performances ever seen on screen, but it is totally in keeping with the character as written. And both he and Nathan Lane (as Costard the clown) bring an essential element of sadness to their otherwise comic roles that is very moving. But the double quartet of lovers that form the central romantic story of the film is a very mixed bag indeed. Branagh understandably gives the plum role of Berowne to himself and sells his Shakespeare with that admirable deftness that is uniquely his, but he is really too old for the part and this works against him here. I also feel at times he should have directed himself more astutely or had better assistance at doing so, for it is largely the scenes in which he does not appear that work best –simply because at such times he, as director, is able to concentrate fully on the other performances. The film also seems unable to break itself totally free from its stageiness to become the truly filmic musical it aspires to be.

So, I am quite ambivalent about this film. I DO like and enjoy it, and applaud Branagh for tackling a lesser-known Shakespeare comedy, and with such gusto, but I SO wish I were able to like it more and be fully satisfied by it –and by the greater film that is in its heart..

Love’s Labour’s Lost (2000)

Director: Kenneth Branagh

With: Kenneth Branagh, Timothy Spall, Alicia Silverstone, Nathan Lane, Matthew Lillard, Geraldine McEwan, Richard Briers, Alessandro Nivola. Adrian Lester

Wednesday, 20 April 2016

LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST –The One With Honorificabilitudinitatibus

And if you are wondering just what on earth ”honorificabilitudinit-atibus” is, it just happens to be longest word found in Shakespeare! A latin construction, it means ”the state of being able to accept honours”, and is uttered more or less as a joke by the character Costard the clown as an ironic counter to some of the long, long sentences of what seems like gobbledegook spoken by the pedantic schoolmaster Holofernes. The word also, apparently, is an anagram of Hi ludi, F. Baconis nati, tuiti orbi –which translates into English as ”These plays, F. Bacon’s offspring, are preserved for the world” –and thus often presented as evidence that Francis Bacon was the true writer of this and all the other plays attributed to Shakespeare. Well, let’s not get into THAT debate right now!

However, the use of honorificabilitudinitatibus does seem to me to point to the salient feature of Love’s Labour’s Lost –one that both demonstrates its uniqueness AND its weakness: its cleverness. For it is a very clever play; too clever for its own good. And by clever I don’t mean in terms of plot, because that is extremely simple, but in its use of language. It is full of playful, witty and tricky twists and turns of language, and so much so that this ultimately gets in the way of a many people’s enjoyment of the play’s genuine sentiments. It is thus an acquired taste, not a play that is digested without close attention, and it is easily dismissed as too obscure for most modern audiences unless heavily edited or adapted. It’s certainly worlds apart from the preceding play The Comedy of Errors and obviously written for a completely different audience, for much of its humour is sophisticated and elaborate, whereas the previous play relied much more on in-your-face situational and farcial comedy for its laughs.

And yet Love’s Labour’s Lost does contains some very funny scenes, and some terrific humoristic characters –including one of Shakespeare’s most interesting creations Don Adriano de Armado –the fantastical Spaniard who seems at first so outrageously over-the-top that laughing at him seems too little, but who then emerges as a character who appeals to our sympathy through his incredibly touching earnestness. A character both comic and melancholic; brash, yet tender, and totally without the cynicism that marks some of Shakespeare’s other comic characters.

Though I have come to admire and appreciate the deftness involved in its writing, I cannot say that this play is among my favourite of Shakspeare’s comedies, and reading it has taken me longer than all the others I have read up until now –simply because the language is so elaborate, and checking meanings at every other word takes away the instant enjoyment of other, more ”flowing”, works. It is a play that demands a lot of the reader/audience on a language level, especially in the comic exchanges, but let’s not forget, this is above all a romantic comedy, and it is in its romantic passages that we, today, probably find most delight. For there are some truly wonderful and beautiful reflections on romance and love and wooing to be found here, and these passages are far more accessible to us than much of the dated comic material. With A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet following this play in the chronology, Shakespeare’s mind is now clearly filled with a need and desire to examine ideas about love and romance, that find expression in such wonderfully different forms. A lost play known only by its title, Love’s Labour’s Won, may have been a continuation of this play, or a further examination of the ways of love, but that's another of those vexing Shakespeare mysteries that we shall probably never know the answer to.

I do recommend anyone wishing to tackle Love’s Labour’s Lost for the first time to read Harley Granville-Barker’s brilliant introduction to the play. His is a practical and sensible viewpoint, valuable to both reader and theatre-goer, and provides a refreshingly readable explanation of much that is obscure in the text. Some of the more academic editions have a field day with this play, with their footnotes covering more page area than the text itself, and though perhaps of interest to dedicated students, these footnotes seem often as bloated as the long-winded utterences of Holofernes himself! In conclusion: not to everybody’s taste, but fascinating nonetheless.

Favourite Line:

Berowne:

And when Love speaks, the voice of all the gods

Make heaven drowsy with the harmony.

(Act IV, Sc.3)

Character I would most like to play: Don Armado

However, the use of honorificabilitudinitatibus does seem to me to point to the salient feature of Love’s Labour’s Lost –one that both demonstrates its uniqueness AND its weakness: its cleverness. For it is a very clever play; too clever for its own good. And by clever I don’t mean in terms of plot, because that is extremely simple, but in its use of language. It is full of playful, witty and tricky twists and turns of language, and so much so that this ultimately gets in the way of a many people’s enjoyment of the play’s genuine sentiments. It is thus an acquired taste, not a play that is digested without close attention, and it is easily dismissed as too obscure for most modern audiences unless heavily edited or adapted. It’s certainly worlds apart from the preceding play The Comedy of Errors and obviously written for a completely different audience, for much of its humour is sophisticated and elaborate, whereas the previous play relied much more on in-your-face situational and farcial comedy for its laughs.

And yet Love’s Labour’s Lost does contains some very funny scenes, and some terrific humoristic characters –including one of Shakespeare’s most interesting creations Don Adriano de Armado –the fantastical Spaniard who seems at first so outrageously over-the-top that laughing at him seems too little, but who then emerges as a character who appeals to our sympathy through his incredibly touching earnestness. A character both comic and melancholic; brash, yet tender, and totally without the cynicism that marks some of Shakespeare’s other comic characters.

Though I have come to admire and appreciate the deftness involved in its writing, I cannot say that this play is among my favourite of Shakspeare’s comedies, and reading it has taken me longer than all the others I have read up until now –simply because the language is so elaborate, and checking meanings at every other word takes away the instant enjoyment of other, more ”flowing”, works. It is a play that demands a lot of the reader/audience on a language level, especially in the comic exchanges, but let’s not forget, this is above all a romantic comedy, and it is in its romantic passages that we, today, probably find most delight. For there are some truly wonderful and beautiful reflections on romance and love and wooing to be found here, and these passages are far more accessible to us than much of the dated comic material. With A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet following this play in the chronology, Shakespeare’s mind is now clearly filled with a need and desire to examine ideas about love and romance, that find expression in such wonderfully different forms. A lost play known only by its title, Love’s Labour’s Won, may have been a continuation of this play, or a further examination of the ways of love, but that's another of those vexing Shakespeare mysteries that we shall probably never know the answer to.

I do recommend anyone wishing to tackle Love’s Labour’s Lost for the first time to read Harley Granville-Barker’s brilliant introduction to the play. His is a practical and sensible viewpoint, valuable to both reader and theatre-goer, and provides a refreshingly readable explanation of much that is obscure in the text. Some of the more academic editions have a field day with this play, with their footnotes covering more page area than the text itself, and though perhaps of interest to dedicated students, these footnotes seem often as bloated as the long-winded utterences of Holofernes himself! In conclusion: not to everybody’s taste, but fascinating nonetheless.

Favourite Line:

Berowne:

And when Love speaks, the voice of all the gods

Make heaven drowsy with the harmony.

(Act IV, Sc.3)

Character I would most like to play: Don Armado

Thursday, 14 April 2016

THE COMEDY OF ERRORS –The One With the Kitchen Wench!

Actually, that’s only partly true, because though the kitchen wench figures in the play, and is drawn as vivid and memorable character as any in Shakespeare’s comedies, she doesn’t actually appear at all! Like the equally memorable (canine), Crab, in The Two Gentlemen of Verona, she is another of those exclusive characters who is merely referred to by others –in this case by the hapless Dromio of Syracuse. His description of the determined, lusty and very large maid is one of the funniest passages in all of Shakespeare, comparing her to a globe and listing the various countries her body parts form. It was actually this scene that first brought me to The Comedy of Errors, for I performed it fairly regularly 25 years ago as part of numerous ”Shakespeare Evenings” presented by my old theatre group, The Oslo Players, and it invariably provoked much delight. I then returned to the play when studying for my literature degree, as one of my chosen exam papers was on Roman Comedy –and in particular Menaechmi by Plautus –the play on which The Comedy of Errors is based. In that play there is one set of twins, with two servants; but Shakespeare develops the comedy to new levels of confusion by making the two servants twins as well! The play is thus perhaps not surprisingly the most farcial of all Shakespeare’s plays. And as it is also the shortest one in the canon and all takes place in the same location and has few props and (unusually for Shakespeare) no music, it is a play very suited to small-scale venues, tours or ”special events”. Indeed, it seems to have been performed originally for a group of law students towards the end of an evening’s programme of diverse entertainment, and no doubt went down very well. The only version I have seen was a musical adaptation developed by the RSC in the 1970s and then ”franchised out” to other producers (the one I saw was a Norwegian production). This was a joyful romp that kept pretty much everything in the play and added songs and dance to flesh out the evening. Rodgers & Hart’s musical The Boys From Syracuse was also inspired by this play.

Though farcial and light, and often therefore dismissed as a mere trifle, there is also seriousness in the play in the back story that caused the twins to be separated in the first place. At times while reading it I felt a similarity to that later, more melancholy comedy, Twelfth Night, which also deals with twins and mistaken identity. And the subject matter was not unfamiliar to Shakespeare as he himself was a father to twins (albeit not identical ones). This surely must have informed him or at least been partly on his mind when dealing with this subject so humorously. And he certainly grasped the potential for confusion and mayhem in his deft handling of the unfolding action –which has to be very precisely staged and directed for everything to work; farce is quite scientific in this way, and Shakespeare certainly knows his stuff, and what works theatrically.

I personally think this play comes earlier in the chronology than is generally listed, and believe it was possibly one of the first Shakespeare wrote. This is more something I felt instinctively upon re-reading it than having any real proof. Certainly it is an early work, both in style, language and maturity of character. But it is skillfully written too, and as the text is now surely must be the result of much trial and error on stage of what works and what doesn’t. It is trim and to the point and there is little here that can be easily cut without ruining the meticulous mechanism of the plot. It is a satisfying, fun read, but to be really enjoyable cries out to be up on stage –far more than some of Shakespeare’s other comedies which work equally well in the armchair!

Favourite Line:

Dromio of Syracuse:

As from a bear a man would run for life

So fly I from her that would be my wife.

(Act III, Sc.2)

Character I would most like to play: Dromio (both of Ephesus and Syracuse)

Though farcial and light, and often therefore dismissed as a mere trifle, there is also seriousness in the play in the back story that caused the twins to be separated in the first place. At times while reading it I felt a similarity to that later, more melancholy comedy, Twelfth Night, which also deals with twins and mistaken identity. And the subject matter was not unfamiliar to Shakespeare as he himself was a father to twins (albeit not identical ones). This surely must have informed him or at least been partly on his mind when dealing with this subject so humorously. And he certainly grasped the potential for confusion and mayhem in his deft handling of the unfolding action –which has to be very precisely staged and directed for everything to work; farce is quite scientific in this way, and Shakespeare certainly knows his stuff, and what works theatrically.

I personally think this play comes earlier in the chronology than is generally listed, and believe it was possibly one of the first Shakespeare wrote. This is more something I felt instinctively upon re-reading it than having any real proof. Certainly it is an early work, both in style, language and maturity of character. But it is skillfully written too, and as the text is now surely must be the result of much trial and error on stage of what works and what doesn’t. It is trim and to the point and there is little here that can be easily cut without ruining the meticulous mechanism of the plot. It is a satisfying, fun read, but to be really enjoyable cries out to be up on stage –far more than some of Shakespeare’s other comedies which work equally well in the armchair!

Favourite Line:

Dromio of Syracuse:

As from a bear a man would run for life

So fly I from her that would be my wife.

(Act III, Sc.2)

Character I would most like to play: Dromio (both of Ephesus and Syracuse)

Wednesday, 6 April 2016

SHAKES-SCREEN: Richard III (1995)

I rate this as one of my favourite Shakespeare films!

Placing one of Shakespeare’s history plays in another specific historical period is always a bit of a risky thing. Such a ploy more frequently works better on stage than on screen –our suspension of belief being somewhat more liberal in a theatre than in front of a screen. Often the transfer in time is to a “generic” future historical setting, with a bit of this period and a bit of that. Sometimes this works, sometimes it doesn’t. The reason I think placing this version of Richard III in the 1930s works so well is the faithfulness to that conceit, which is carried through impeccably in every detail, though never in a forced or laboured way. It is a clever, often witty, adaptation of Shakespeare’s masterly examination of one man’s relentless pursuit of power –and has both elegance and a style of its own aside from the play it is based on, and a healthy respect of Shakespeare’s glorious language and characters.

Perhaps the language is what may deter some people from fully enjoying this, though I would argue that it merely demands paying a little more attention to what is being said than when watching a “normal” film. Contrary to what many may think, Shakespeare’s language is not difficult or obscure –quite the opposite– but you do need to listen to it! Here, of course, you are helped by having some of the finest actors around, with not only great command of that language, but the ability to present clearly defined yet complex characters, so that we are able to keep track of who is who in the web of family connections and intrigue. The film is much shorter than the play (Shakespeare’s longest), and does away with some characters and combines others into one figure. This polishes the narrative somewhat, but does not take anything vital away from the unfolding tale. I do, however, recommend going back to the original play if you enjoy this film, because it will give an even broader appreciation of the story. And what a story!

Centre-stage (or centre-screen, in this case) is Ian McKellen as Richard. It is surely his finest screen performance, and is certainly the one that really made me appreciate his work when I first saw the film upon its original release. Like Olivier before him, his Richard is a performance perfected through countless performances on stage in the role, and with devilish charm he milks each ounce of scheming, determination and wickedness from his scenes. Yet, unlike Olivier, he also shares with us a certain clumsiness and even pathos, which though it does not excuse in any way his actions does give us some understanding of why he has become the grotesque figure he is.

Of the other performances I particularly like Jim Broadbent’s take on the Duke of Buckingham –his beaming face has eyes of steel, and he seems to be silently scheming, listening, and judging in every scene in which he appears. Anette Bening also does a terrific job and makes more much of her part than is written. But all the actors do wonders in conveying their own particular “angsts” and concerns. Seeing the film again now, I only wish it was longer and we saw even more of some of them.

Finally I must applaud the designers of the production –both visual and aural– who have created a totally believable alternate English setting of the 1930s. It is both familiar and alien at the same time –which is what makes the film’s central idea so chilling: That such a thing could have happened in England at this time as it did in Germany and Italy and Spain. Shakespeare may have been writing about the 15th century, but the scheming of despots, hungry for power, goes on and on and on.

Richard III (1995)

Director: Richard Loncraine

With: Ian McKellen, Nigel Hawthorne, Anette Bening, Maggie Smith, Jim Broadbent, Robert Downey, Jr.

Placing one of Shakespeare’s history plays in another specific historical period is always a bit of a risky thing. Such a ploy more frequently works better on stage than on screen –our suspension of belief being somewhat more liberal in a theatre than in front of a screen. Often the transfer in time is to a “generic” future historical setting, with a bit of this period and a bit of that. Sometimes this works, sometimes it doesn’t. The reason I think placing this version of Richard III in the 1930s works so well is the faithfulness to that conceit, which is carried through impeccably in every detail, though never in a forced or laboured way. It is a clever, often witty, adaptation of Shakespeare’s masterly examination of one man’s relentless pursuit of power –and has both elegance and a style of its own aside from the play it is based on, and a healthy respect of Shakespeare’s glorious language and characters.

Perhaps the language is what may deter some people from fully enjoying this, though I would argue that it merely demands paying a little more attention to what is being said than when watching a “normal” film. Contrary to what many may think, Shakespeare’s language is not difficult or obscure –quite the opposite– but you do need to listen to it! Here, of course, you are helped by having some of the finest actors around, with not only great command of that language, but the ability to present clearly defined yet complex characters, so that we are able to keep track of who is who in the web of family connections and intrigue. The film is much shorter than the play (Shakespeare’s longest), and does away with some characters and combines others into one figure. This polishes the narrative somewhat, but does not take anything vital away from the unfolding tale. I do, however, recommend going back to the original play if you enjoy this film, because it will give an even broader appreciation of the story. And what a story!

Centre-stage (or centre-screen, in this case) is Ian McKellen as Richard. It is surely his finest screen performance, and is certainly the one that really made me appreciate his work when I first saw the film upon its original release. Like Olivier before him, his Richard is a performance perfected through countless performances on stage in the role, and with devilish charm he milks each ounce of scheming, determination and wickedness from his scenes. Yet, unlike Olivier, he also shares with us a certain clumsiness and even pathos, which though it does not excuse in any way his actions does give us some understanding of why he has become the grotesque figure he is.

Of the other performances I particularly like Jim Broadbent’s take on the Duke of Buckingham –his beaming face has eyes of steel, and he seems to be silently scheming, listening, and judging in every scene in which he appears. Anette Bening also does a terrific job and makes more much of her part than is written. But all the actors do wonders in conveying their own particular “angsts” and concerns. Seeing the film again now, I only wish it was longer and we saw even more of some of them.

Finally I must applaud the designers of the production –both visual and aural– who have created a totally believable alternate English setting of the 1930s. It is both familiar and alien at the same time –which is what makes the film’s central idea so chilling: That such a thing could have happened in England at this time as it did in Germany and Italy and Spain. Shakespeare may have been writing about the 15th century, but the scheming of despots, hungry for power, goes on and on and on.

Richard III (1995)

Director: Richard Loncraine

With: Ian McKellen, Nigel Hawthorne, Anette Bening, Maggie Smith, Jim Broadbent, Robert Downey, Jr.

Monday, 4 April 2016

THE RAPE OF LUCRECE –STILL DISTURBING

I first read Shakespeare’s The Rape of Lucrece many years ago when I was a teenager, and passed over it pretty quickly because at that time I was more interested in the plays, but I returned to it a few years ago when I worked as language/text coach on The Norwegian Opera’s production of Benjamin Britten’s The Rape of Lucretia. The libretto for that was written by Ronald Duncan, based on a French play by André Obey. The story though is essentially the same in all these versions, and stems from the classical tale as told by Ovid in Fasti and Livy in his History of Rome. The opera fleshed out the narrative somewhat, introducing characters who are only mentioned in Shakespeare’s version, and staged much more of the pretext to the unfortunate act of transgression. Shakespeare does away with most of this background in a prose ”Argument” printed before the start of the poem, thus diving straight into the central action of the piece: The rape of Lucrece.

Thus, the poem concerns almost entirely the two main characters –the unfortunate Lucrece, and her husband’s supposed friend Sextus Tarquinius who forces himself upon her. The first part of the long poem belongs to him, the second to Lucrece. It’s at times a hard, disturbing read, and as a poem it is both a serious counter-poem to the frothier, mythological Venus and Adonis that precedes it, and a harbinger of some of the tragedies to come. Like Venus and Adonis it is essentially a drama, with lots of action and talking and atmosphere, but its power lies in Shakespeare’s brilliant, succinct language. It’s more direct, less playful than in the former poem, yet brimming with astounding pictures and a true command of the sounds of particular words. It is here I really start to sense the skillful way Shakespeare uses vowel sounds to convey various emotions –which he puts to use so brilliantly in many of the plays that follow. And I feel Shakespeare has worked hard on this piece –By that I don’t mean that it seems laboured, but more considered and weighty than the delightful musicality of Venus and Adonis. Like all of Shakespeare it is best served when read aloud, and each 7-line verse is a miniature drama of its own. (Venus and Adonis had verses of 6 lines, so the rhythm here is quite different, though both poems, like the sonnets, pack their punch into the final couplet of each verse.

When working on the opera there was relatively little I could use from Shakespeare to illuminate the Ronald Duncan text or Britten’s music, but it was intriguing to see how such different creative forces tackled essentially the same story. Duncan’s text clarified much that was difficult or obscure in Shakespeare (who is guilty of some digression here and there it must be said), and Britten’s haunting music captured what Shakespeare managed with mere music of words and poetry.

This work, like Venus and Adonis before it, was enormously popular in Shakespeare’s own time and saw many re-printings in his lifetime. Nowadays, hardly anyone bothers to read it (do they read long poems at all?), and admittedly it is not at all a ”feel-good” read. But it is gripping, disturbing, sad, tragic and moving. And you are encountering a master poet and dramatist in one.

Favourite Line:

Brand not my forehead with thy piercing light,

For day hath naught to do what’s done by night.

Thus, the poem concerns almost entirely the two main characters –the unfortunate Lucrece, and her husband’s supposed friend Sextus Tarquinius who forces himself upon her. The first part of the long poem belongs to him, the second to Lucrece. It’s at times a hard, disturbing read, and as a poem it is both a serious counter-poem to the frothier, mythological Venus and Adonis that precedes it, and a harbinger of some of the tragedies to come. Like Venus and Adonis it is essentially a drama, with lots of action and talking and atmosphere, but its power lies in Shakespeare’s brilliant, succinct language. It’s more direct, less playful than in the former poem, yet brimming with astounding pictures and a true command of the sounds of particular words. It is here I really start to sense the skillful way Shakespeare uses vowel sounds to convey various emotions –which he puts to use so brilliantly in many of the plays that follow. And I feel Shakespeare has worked hard on this piece –By that I don’t mean that it seems laboured, but more considered and weighty than the delightful musicality of Venus and Adonis. Like all of Shakespeare it is best served when read aloud, and each 7-line verse is a miniature drama of its own. (Venus and Adonis had verses of 6 lines, so the rhythm here is quite different, though both poems, like the sonnets, pack their punch into the final couplet of each verse.

When working on the opera there was relatively little I could use from Shakespeare to illuminate the Ronald Duncan text or Britten’s music, but it was intriguing to see how such different creative forces tackled essentially the same story. Duncan’s text clarified much that was difficult or obscure in Shakespeare (who is guilty of some digression here and there it must be said), and Britten’s haunting music captured what Shakespeare managed with mere music of words and poetry.

This work, like Venus and Adonis before it, was enormously popular in Shakespeare’s own time and saw many re-printings in his lifetime. Nowadays, hardly anyone bothers to read it (do they read long poems at all?), and admittedly it is not at all a ”feel-good” read. But it is gripping, disturbing, sad, tragic and moving. And you are encountering a master poet and dramatist in one.

Favourite Line:

Brand not my forehead with thy piercing light,

For day hath naught to do what’s done by night.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)